By Stephen Musk and Roger Mann, Troubador, pp xiv+313, £25, ISBN 9781803131221

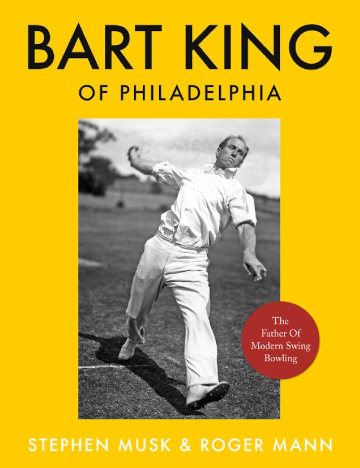

Occasionally – very occasionally – a book comes along which ticks all one’s personal boxes; and then, even more rarely, not only ticks these boxes but introduces some more for consideration. Bart King of Philadelphia is one such experience for the reviewer; and I say ‘experience’ because the enjoyment of a book not only inheres in the text itself but also the way in which it is presented. This publication boasts a weighty dust wrapper, gilt lettering to the red boards, high quality paper and an abundance of wonderful illustrations.

It is clear that, to use the expression of an old tutor of mine, Stephen Musk has fallen in love with his subject – a prerequisite to completing any research. He describes the journey he has been on over the past 30 years in discovering all he can about John Barton King, and how he came to collaborate with Roger Mann on this work. In respect of the subject, it is well contextualised; Musk does not patronise his readers but neither does he assume a certain level of knowledge. He is sensitive in introducing issues, such as (facing page xiii) the illustration of the cover of the final edition of The American Cricketer in 1929, with the caption, ‘The curtain went down on cricket in Philadelphia’. My immediate question was, ‘Why did the curtain fall?’ – and, beginning on p205, Musk offers some answers, but has kept the pot bubbling in between.

In respect of cricket failing to develop a national identity in America and a desire to make the game more like baseball in its pace and outcome – apparently, the concept of a draw was anathema to the cricket legislators of the day – several tweaks were considered; which puts me in mind of the ‘big bash’ cricket of today and the thinking behind such innovations as the ‘Hundred’ matches. Quicker, louder, brasher – and a sword in the side of traditionalists. It is in raising questions like this, whether intentionally or not, that this book demonstrates its relevance today, regardless of the fact that ostensibly the subject matter is American cricket and, more specifically, the ‘Philadelphia Story’ (Grace Kelly does not feature, alas!).

Specifically, as regards the subject matter, it is well contextualized so that King’s achievements can be fully appreciated; the text is well written and superbly illustrated with relevant images – including a wonderful series of King’s swing bowling action – from Mann’s extensive collection of photographs; there is a useful bibliography, a comprehensive index, and the clear and concise presentation of relevant statistics. I am emphasizing ‘relevance’ as so many publications nowadays stray from their subject matter with extraneous details. In this book, as the narrative builds, so does one’s appreciation of the contribution of Bart King both as an individual and a team player. There are charming pen-portraits of the cricketer in later life, as an accomplished after-dinner speaker, possessed of an ironic but never unkind sense of humour; someone who lived his life to the full while never losing his love of the game.

One test of a good book is whether it can fall open at a random page and see if (i) what I am reading makes sense in the wider context; and (ii) I learn something new or, at least, am encouraged to question what I believe I already know. This book delivers on both; and it would be a great addition to the bookshelf of anyone interested in the game of cricket, whether generally or as a social / statistical historian.

Roger Heavens (The Cricket Statistician, Autumn 2022)