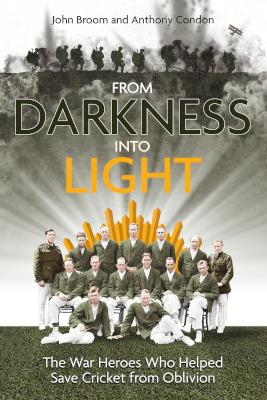

By John Broom and Anthony Condon, Pitch Publishing, pp 352, £25, ISBN 9781801504423, e-book £9.99

Military historian (and ACS member) John Broom has written several books that have been reviewed in these pages in recent years, notably his valuable accounts of cricket during the two world wars. He has followed this up with an account of the tour of England by the Australian Imperial Forces XI immediately after the First World War in 1919. His co-author, Australian academic Anthony Condon, is perhaps less well known on this side of the world, but some of his written and podcast material, including a fictional set of diaries of the 1919 tour and a downloadable copy of his doctoral thesis on The Gentleman’s Game, can be found on his website, www.anthonycondon.com.

The book has a slightly unusual structure. The Introduction, which I understand to have been largely the work of Anthony Condon, would normally be expected to cover perhaps a dozen pages. This one runs to over a hundred, forming about a third of the book’s total content, and in truth is rather more than just an introduction to the main substance of the volume. It includes a thorough investigation into the somewhat obscure background to the tour, which at one stage was intended to be a full Australian cricket tour, complete with Test matches. The process by which it became a private tour under military auspices makes fascinating reading, all the more so as this is not a well-known period of cricket history.

The second part of the book is an account of the tour itself, beginning, after a brief excursion to Norfolk for the opening fixture, with the match against Essex at Leyton. As the title suggests, the central thesis of the book is that of cricket passing from the darkness of the First World War to the light of the post-war period, and there is something strangely moving in the simple report that over four thousand people paid for admission on the opening day of the match. A reader expecting a simple set of match reports in this section of the book will have his expectations challenged. With each stop on the journey, the authors pause for reflection. So, the chapter on the match against Hampshire, for example, looks in detail at the impact of the War on ‘this most military of English counties’, while the chapter on Yorkshire describes the division between the county club and the Bradford League during the War. Indeed, a description of the play itself often comprises less than half the chapter’s contents, which is not intended to be a criticism, as the book captures the state of English cricket in that troubled time.

As an aside, it is worth noting that although the book is nicely produced in hardback with a dust jacket, the photographic section is printed on ordinary paper, not glossy paper as is usually the case. I have noted this with a number of books from this publisher this year, presumably as a cost-cutting exercise, understandable in the current economic climate. My feeling is that the photos do not reproduce so well in this form, and I hope this will be a temporary move.

Unlike some parts of cricket history, this is not a tour that has attracted much coverage from historians; no material on the tour has crossed my desk in the last fifteen years, and indeed I cannot think of anything else on the tour apart from a book by Ronald Cardwell more than forty years ago, now almost impossible to obtain. So this detailed and well researched account is a very welcome addition to the library.

Richard Lawrence (The Cricket Statistician, August 2023)